If we want schools to be safe for all kids, we cannot ignore the direct connections between bullying, sexual harassment and homophobic name-calling in middle school. That’s according to groundbreaking research presented by University of Florida psychology professor Dorothy Espelage in her latest talk. One of the U.S.’s leading bullying researchers, she was speaking in Washington at the American Psychological Association, which just honored her with a lifetime achievement award.

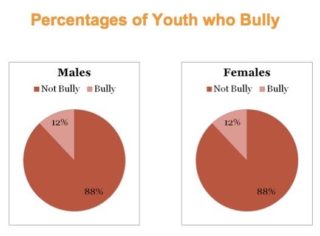

“Bullying leads to homophobic name-calling,” which is prevalent in middle school, Dr. Espelage said, “and it also predicts sexual harassment perpetration in middle school” and high school, as well as dating violence in high school and then colleges and universities.

“Bullying leads to homophobic name-calling,” which is prevalent in middle school, Dr. Espelage said, “and it also predicts sexual harassment perpetration in middle school” and high school, as well as dating violence in high school and then colleges and universities.

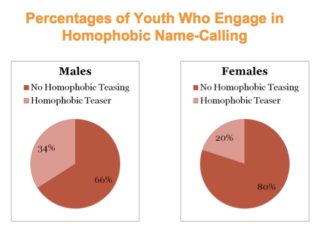

A major new study by Harris Poll for GLSEN found that 55% of students aged 13-18 hear peers saying “that’s so gay” often or very often, 43% other homophobic terms often or very often, and a quarter (25.5%) hear school staff “make negative remarks related to students’ gender expression.”

Factor gender into bullying prevention

Espelage and her colleagues have found that students as young as 5th and 6th graders commonly use that terminology, as many parents know – “especially when boys do not act masculine and girls do not act feminine,” as kids collectively define those terms in their own peer groups and schools. “We found that such homophobic language is used to assert power over other students…. [They] start to sexually harass members of the opposite sex to demonstrate that they are not gay,” she wrote.

For that reason, even though most bullying prevention programs don’t factor in gender, they need to, she said in her talk. “We have to recognize that this socialization process, this homophobia and sexual harassment that happens to both boys and girls happens way before we send them to college.

For that reason, even though most bullying prevention programs don’t factor in gender, they need to, she said in her talk. “We have to recognize that this socialization process, this homophobia and sexual harassment that happens to both boys and girls happens way before we send them to college.

“If we continue to do this [bullying prevention] work in schools with no gender lens, we’re going to continue to fall short,” she said. On the other hand, “if we address homophobic name-calling … we’ll have much improved lives for middle school students, and [this prevention work] will be relevant to them [emphasis mine].” She mentioned one brave 7th grader who told her that he was just so done with the name-calling and didn’t understand why the questions the researchers were asking them didn’t look at the kind of aggressive behavior that irritated and disturbed students like him the most.

Other key highlights from a very comprehensive talk:

- Social emotional learning is powerful: “Out of the gate, after just 15 lessons” (out of 41 SEL lessons that 3,600 6th-8th-graders received over a three-year study), her research turned up a “major reduction in physical fighting”: 42%, “where most programs predict a 3% reduction,” she said. “By Year 3, Second Step [the SEL program they used in the study] had reduced all forms of victimization – including for kids with a disability.” The findings reinforced what many of us have come to see, including me: that SEL instruction would benefit every student and every school, especially now that social media is part of the school climate mix. Social literacy training for social media (and life!). In her talk, Espelage also pointed to studies showing SEL’s positive impact on students’ academic performance as well as school climate, “and it works at multiple levels of society.” [Here‘s what SEL teaches.]

- Positive school climates, safe students: SEL, bullying prevention, mindfulness, etc. “We can have all these programs, but we have to understand the larger school climate…. We’ve ignored the adult component – teachers, administrators, superintendents. “You really can’t have the social-emotional competencies in kids if you don’t have them in teachers,” she said, pointing to the need for teachers’ professional development in SEL too. “I [as a student] can have a predisposition to be aggressive, but if I’m in a classroom where the norm is to be pro-social, [that predisposition] will not be turned on,” she said, saying the reverse can be true too, of course. “My individual propensity interacts with classroom norms and ultimately school climate.”

- If we want students to be “upstanders”: In visits to schools all over the country, Espelage found that, when teachers said they had a social aggression problem in their schools, the students said they didn’t intervene. “We can’t tell kids to intervene if it’s not a safe space,” she said, referring to classrooms as well as school in general. And it has to be a safe space for teachers as well, in this sense: “If teachers feel supported by their school’s administration to do this work in the classroom, the kids are saying aggression is happening less.” They’re bullied less, victimized less, and they fight less. “That’s powerful,” Espelage said, while acknowledging that it’s not easy to make this happen because it’s a multi-level process, but it’s worth it – rewarding for everybody. “You’re not going to be perfect, nothing’s perfect. But go after this – so the kids can perceive you’re doing something, and then they’ll be more caring toward one another.”

- Taking “the punishment route” doesn’t work. “Principals are very challenged,” Espelage said, because they’re often pressured to use the punitive approach by parents or victims. But progress comes from adults’ supportive responses and modeling of respectful behavior – a huge part of improving school climate. This will have a positive impact on cyberbullying too, she said. “My hope is that, as we create more positive school climates, where kids are bullying and engaging in other forms of aggression less, then when they go into that other [digital] space, that prosocial behavior will be reflected,” she said.

-

Chart from Dr. D. Espelage A healthy school looks like a healthy family and vice versa (see Espelage’s slide to the right for the characteristics of “healthy” in both cases).

- Cyberbullying’s context isn’t social media. Seriously. “What I hear all the time from schools is that ‘social media is wreaking havoc’,” Espelage said. But addressing content or behavior in social media doesn’t reduce cyberbullying nearly as much as addressing bullying, homophobic name-calling and gender-based harassment, she said. “Having the attorney general come to school to talk to students” about social media doesn’t really help reduce cyberbullying, she said. That’s because the context of cyberbullying is really young users’ school climate, what’s happening in their peer groups, not media. Bullying predicts cyberbullying more than social media use does. This was a key finding from a lit review produced by a national task force I served on: that a child’s psychosocial makeup and home and school environments are better predictors of online risk than any technology the child uses.

- If a student comes to you: “Just assume when a kid comes to you and says ‘I’m being bullied, I’m being victimized’ – and of course you’re going to ask them what’s happening, because ‘bullying’ doesn’t really mean much…from Student A to Student B – assume it’s been happening for a while…ask them if they feel they can defend themselves. If they say no, then ask, ‘Who can you turn to, do you feel helpless?’ In some cases, especially LGBT youth, we’re starting to chase after this notion of feeling like a burden to their family. So understanding that some kids feel so depressed and withdrawn when they’re victimized because they don’t want to tell their parents again; their parents thought it stopped…and their mom’s having to take off of work and come down to school…. So the burden piece is showing up to be quite relevant as well…. So we have these components: If it’s been happening for awhile, they feel defenseless, they have no one to turn to, be concerned and do a referral.”

So 1) bullying prevention work needs to reach young people when or before they’re doing their developmental identity formation, which includes gender identity and 2) everybody in the school community has a role in creating a climate of dignity and respect. And 3) when schools decide not to tolerate sexual harassment of any student, they’ll see less homophobic name-calling, more gender equity and less sexual harassment. 4) They’ll also see less cyberbullying, which is bullying happening in what has become just another space where students’ interaction plays out. 5) Punitive doesn’t work: Not only is it clearer than ever that pressure on administrators to suspend and expel not only does nothing to make schools safer, it sends the message that power – which is a component of both punitive responses and bullying – is what solves social problems. It doesn’t. And 6) we now have solid, multi-year research showing that social emotional learning is powerful prevention. It reduces “all forms of victimization,” even for the most vulnerable students, and improves school climate.